Honoring Three Influential Scientists for Black History Month

Wednesday, February 17, 2021 written by Leanna Read

In honor of Black History Month, we wanted to share our appreciation for three brilliant scientists who have contributed to fields of conservation or biology. All three demonstrate the core Aquarium message that we are all connected, as parts of one global ecosystem, and demonstrate the curiosity and tenacity it takes to be an influential scientist.

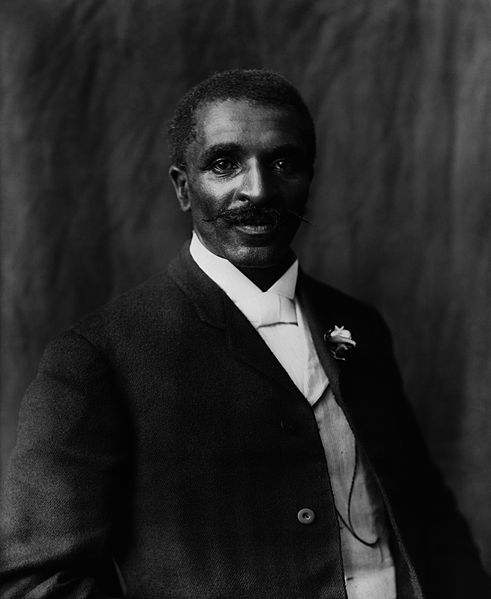

George Washington Carver (1864-1943)

“I wanted to know the name of every stone and flower and insect and bird and beast. I wanted to know where it got its color, where it got is life—but there was no one to tell me.”

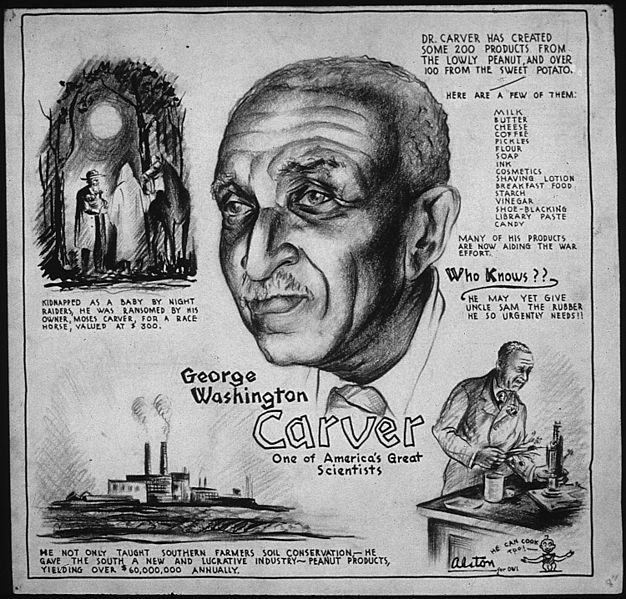

George Washington Carver, dubbed the “Black Leonardo” by Time magazine in 1941, was an agricultural researcher whose work on crop rotation has boosted conservation efforts by improving the yield and productivity of farms. He is most known for creating over 200 useful products from peanut and potato plants, some examples of which can be seen in the World War II poster pictured below. Carver was born into slavery a year before it was outlawed. He left home at a young age to pursue academics and earned a master’s degree in agricultural science from Iowa State University. (history.com)

Carver was one of the earliest scientists to evaluate agricultural systems through the lens of biomimicry, which refers to man-made product designs that are inspired by nature, such as swimsuits inspired from the denticles of shark skin. Carver observed that nature does not leave waste—everything consumed is returned to the ecosystem in a new, usable form, and balance is maintained. This led to Carver’s breakthroughs in resource conservation and soil preservation. High-yielding farms that use the minimum amount of space are an important part of conserving natural habitats and resources across the globe.

Carver’s beliefs about the unity between everything in the natural world align with the Aquarium’s message that every ecosystem and their inhabitants are connected into one global ecosystem. He understood that, even in the remote corners and depths of the world, nothing exists in isolation, and ignoring that fact leads to disastrous results. Carver taught that every action must be considered in light of its overall long-term consequences, not just its immediate benefits. (sfenvironment.org)

Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941)

“We feel the beauty of nature because we are part of nature and because we know that however much in our separate domains we abstract from the unity of Nature, this unity remains. Although we may deal with particulars, we return finally to the whole pattern woven out of these.”

Ernest Everett Just is considered to be the first black American marine biologist. He excelled in Zoology at Dartmouth College and went on to lead the department of zoology at Howard University. While teaching, he continued his education to obtain a PhD in biology and began his research at Woods Hole to study fertilization and embryology.

Pioneering the science of cell biology, fertilization, and biochemistry, Dr. Just is celebrated for his methods of paying rigorous attention to the natural environment of living-developing-procreating specimens instead of traditional methods of extracting and killing specimens from their environment for research purposes. These methods mark him as an early researcher in developmental biology and ecosystems. (howard.edu)

In 1929 Dr. Just was invited to take his research to Europe—in Naples he experimented with sea urchins, and then in Berlin he continued his studies with other species. When the Nazi invasion reached France in 1940, Dr. Just returned to Howard University, which was one of the institutions that would hire black scientists at the time. (asu.edu)

Roger Arliner Young (1899-1964)

“Not failure, but low aim is a crime.”

Roger Arliner Young was the first black American woman to earn a doctorate degree in Zoology. Young grew up in Pennsylvania and attended Howard University in 1916 to study music. She graduated in 1923 with a B.S. in Zoology and went on to earn a Master’s from the University of Chicago. While at Howard University, Young worked with Dr. Ernest Just for many years. She never appeared as a coauthor on his publications. But in 1924, she published her first article in the journal Science about her discovery of the structure of Paramecium (a species of water-dwelling single-celled organisms), making her the first black American woman to research and publish in the field of Zoology. In 1940 she earned her doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania. (oceanconservancy.org)

In addition to the struggles that a black woman faced in pursuing an academic career in the early 20th century, Young was burdened from having to care for her mother and issues with mental health. Despite these obstacles, Young’s achievements in her field mark her as a model of perseverance and determination. (sdsc.edu)

In 2005, Roger Arliner Young was recognized in a Congressional Resolution along with four other black American women “who have broken through many barriers to achieve greatness in science.” (congress.gov)